Last time we left off with a (pretty empty) backdrop for the ray tracing scene. With ray functionality and a basic camera implemented, our focus shifts to actually rendering some primitives. And to do that, we need to talk about intersections. Also math. Lots, and lots of math… But it will be fun, I promise!

Rather plane

Let’s kick things off with the implementation of an infinite plane, as it is simple to construct. One of the many ways to express an infinite plane is defined by the following function:

\[P \cdot \overrightarrow{N} + d = 0\]Where $P$ is a point in 3D space, $\overrightarrow{N}$ the normal vector of the plane and $d$ a scalar offset.

You might be wondering what a “normal vector” is at this point; in short, it is a vector whose direction is perpendicular to a certain surface - in this case, the surface of a plane. Normals are used absolutely everywhere in graphical applications. For now this quick introduction will suffice though.

Note that a normal vector and the act of “normalizing” a vector (ensuring that the length of a vector is equal to 1) are two very different concepts!

Perhaps you recall from the last post that the ray equation is defined as $P(t) = O + t\overrightarrow{D}$, giving us a point in 3D space along the ray. Due to one of the many cool properties of mathematics, we can substitute for $P$ in the plane equation by plugging in the ray formula:

\[(O + t\overrightarrow{D}) \cdot \overrightarrow{N} + d = 0\]To figure out whether a ray intersects with the plane, we need to find a value for $t$ which satisfies this formula. In other words, by isolating $t$ in the equation we’ll find exactly what we’re looking for:

\[\rightarrow O \cdot \overrightarrow{N} + t\overrightarrow{D} \cdot \overrightarrow{N} + d = 0\] \[\rightarrow t\overrightarrow{D} \cdot \overrightarrow{N} = -(O \cdot \overrightarrow{N} + d)\] \[\rightarrow t = -(O \cdot \overrightarrow{N} + d) / (\overrightarrow{D} \cdot \overrightarrow{N})\]Great! Let’s translate this final equation into code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

// returns "true" if the ray intersects the plane, false otherwise

bool intersect_plane(const ray& r, const float3& normal, float offset)

{

// D . N -> to avoid division by zero,

// if the calculated value is close to zero return false

float denominator = dot(r.direction(), normal);

if (abs(denominator) < 0.00001f) return false;

// O . N + d

float numerator = dot(r.origin(), normal) + offset;

// -(O . N + d) / (D . N)

float t = -numerator / denominator;

// if t is zero or positive, the ray intersects the plane

return t >= 0.0f;

}

Now to expand the ray_color function just a tad in order to check for an arbitrary plane in the scene:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

color ray_color(const ray& r)

{

// check if the current ray intersects a plane with its normal pointing upwards,

// and the plane offset slightly down from the camera

if (intersect_plane(r, float3(0.0f, -1.0f, 0.0f), 1.0f))

// return green as a color when there is an intersection

return color(0.0f, 1.0f, 0.0f);

// if there is no intersection, render the background as usual

// background code here...

}

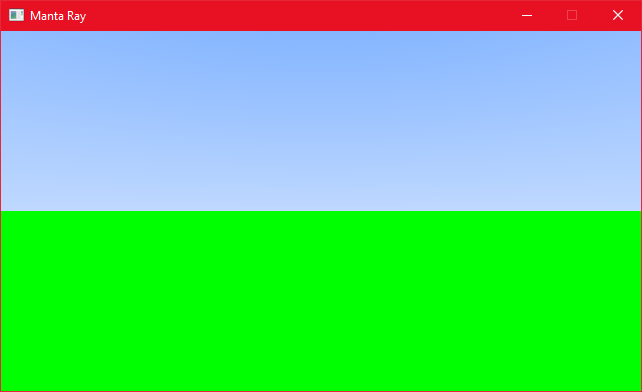

Running the application now gives us an infinite plane rendered all the way towards the horizon (a grassy field, if you will). And with that… The first intersection implementation is finished!

Mr. Blue Sky, meet Mr. Green Field.

Mr. Blue Sky, meet Mr. Green Field.

Abstraction

Sweet, we implemented a way to intersect a ray with a plane. But what if we want to check several planes? Do we need to describe a specific condition for each of them? What happens when we also want to add spheres or triangles as intersectable primitives? If we carry on like this, we’ll end up with an unmanageable mess of spaghetti code which would be hard to maintain in the future…

Luckily, many object-oriented programming languages such as C++ have built-in features to add layers of abstraction. If we think about it, we don’t really care about what a ray intersects with; there should just be function defined for each primitive which handles that intersection for us. As such, each of the primitives/objects we implement needs some kind of intersection method. Furthermore, we should track a set of variables that describes the intersection, like the intersection point, the normal vector at that intersection and the value for $t$ at that intersection. Time to cram all this stuff in an abstract, intersectable class:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

#pragma once

// this struct holds the data which is saved when a ray intersection happens

struct intersect_data

{

float t;

float3 point;

float3 normal;

};

// an abstract class which describes primitives/objects which can be intersected

class intersectable

{

public:

virtual bool intersect(const ray& r, intersect_data& data, float t_min, float t_max) const = 0;

};

The abstract

intersectmethod also takes two scalar values,t_minandt_max. These will be used to define an interval for which the intersection is valid. This will be useful in the future!

How do you like your normals?

There’s a small design decision to make regarding normal vectors. A normal can point outwards or inwards, depending how you look at the surface. For example, how do we handle a normal when we look at the backside of a plane?

As of now, the normal always points outwards from the surface. Another possibility is to always point the normal vector against the ray direction. In this case the normal will point outwards when we are in front of a surface, and inwards when we are on the backside of a surface.

Eventually we want to know which side of the surface we’re facing to apply the rendering in a correct manner. For this application I have chosen to always point the normal against the incident ray, as this allows us to save the information together with the intersection data.

We’ll add a boolean to the intersection data which indicates whether the current intersection is from the front or the back of the surface, in turn flipping the normal accordingly via a function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

// this struct holds the data which is saved when a ray intersection happens

struct intersect_data

{

float t;

float3 point;

float3 normal;

// check whether we are currently in front or behind/inside of the object,

// flipping the normal accordingly

bool front;

inline void set_front(const ray& r, const float3& outward_normal)

{

// the dot product is negative if the ray direction and normal have opposite directions

front = dot(r.direction(), outward_normal) < 0.0f;

// possibly flip the normal direction if we are behind/inside the object

normal = normalize(front ? outward_normal : -outward_normal);

}

};

Re-implementing infinite planes

With the abstract class in place for primitive/object intersection, we can rewrite our infinite plane implementation. First, I defined a new constant which denotes a very small floating point number. This will be useful in a lot of situations:

1

#define EPSILON 0.00001f

I also added an additional function which checks whether a value lies between two other values or not:

1

inline bool between(float f, float a, float b) { return clamp(f, a, b) == f; }

The new plane class inherits from the abstract intersectable class as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

#pragma once

class plane : public intersectable

{

private:

float3 m_normal;

float m_offset;

public:

plane() {}

plane(float3 normal, float offset) : m_normal(normalize(normal)), m_offset(offset) {}

virtual bool intersect(const ray& r, intersect_data& data, float t_min, float t_max) const override;

};

It holds a normal and an offset needed to define a plane. It has a more specific implementation of the intersect method as well; the code is basically the same as before, with some minor edits to save/update the intersection data:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

#include "precomp.h"

bool plane::intersect(const ray& r, intersect_data& data, float t_min, float t_max) const

{

// D . N -> to avoid division by zero,

// if the calculated value is close to 0 (ray parallel with plane) return false

float denominator = dot(r.direction(), m_normal);

if (abs(denominator) < EPSILON) return false;

// O . N + d

// -(O . N + d) / (D . N)

float numerator = dot(r.origin(), m_normal) + m_offset;

float t = -numerator / denominator;

// reject t if the value doesn't lie between the given boundaries

if (!between(t, t_min, t_max)) return false;

// update the intersection data

data.t = t;

data.point = r.point(t);

data.set_front(r, m_normal);

// the ray intersected with the plane

return true;

}

Now that’s all out of the way, we can update mantaray.cpp to use the plane object and the underlying intersect method instead:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

plane p;

// anything that happens only once at application start goes here

void mantaray::Init()

{

p = plane(float3(0.0f, -1.0f, 0.0f), 1.0f);

}

// returns a background gradient depending on the y direction of a primary ray

color ray_color(const ray& r)

{

// check for a ray/plane intersection, return green if they intersect

intersect_data temp_data;

if (p.intersect(r, temp_data, 0.0f, LARGE_FLOAT))

return color(0.0f, 1.0f, 0.0f);

// if there is no intersection, render the background as usual

// background code here...

}

Running the application now produces the same result as before, but on the back-end things have been tidied up and are ready for expansion!

Gettin’ spherical

So let’s expand! Next on the list of primitives to implement is a good ol’ sphere. Once again it will inherit from the abstract intersectable class.

Instead of a normal and an offset, a sphere is defined by its center position and a radius. Aside from that, the class implementation is pretty much identical to that of the infinite plane:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

#pragma once

class sphere : public intersectable

{

private:

float3 m_center;

float m_radius;

public:

sphere() {}

sphere(float3 center, float radius) : m_center(center), m_radius(radius) {}

virtual bool intersect(const ray& r, intersect_data& data, float t_min, float t_max) const override;

};

Implementing the sphere intersect method

Now for the special version of the ray/sphere intersect function. Lo and behold, there exists an equation to describe a sphere with a radius $r$ centered at the origin:

This states that any point $P$ is on the sphere’s surface if the equation holds. The point is inside the sphere if $P^2 \lt r^2$ and the point is outside the sphere if $P^2 \gt r^2$.

However, the sphere isn’t necessarily located at the origin but at any point $C$, so we need to update the formula a bit:

\[(P - C)^2 = r^2\]Which is equal to (dot product rule):

\[(P - C) \cdot (P - C) = r^2\]Once again we can substitute P for the ray equation $P(t) = O + t\overrightarrow{D}$, leaving us with this:

\[(O + t\overrightarrow{D} - C) \cdot (O + t\overrightarrow{D} - C) = r^2\]Time to further expand this equation and solve it with the magic that is vector algebra. I will spare you the details, but eventually we end up with this quadratic formula:

\[\overrightarrow{D} \cdot \overrightarrow{D}t^2 + 2\overrightarrow{D} \cdot (O - C)t + (O - C)^2 - r^2 = 0\]If you weren’t vast asleep during math class at high school, you probably ran into the abc-formula before which we can use to solve quadratic functions:

\[t = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 - 4ac}}{2a}\]Simply plugging in the abc terms using the quadratic function we found gives:

\[a = \overrightarrow{D} \cdot \overrightarrow{D}\] \[b = 2\overrightarrow{D} \cdot (O - C)\] \[c = (O - C)^2 - r^2\]Now we can solve the formula to find a value for $t$. It can have 0, 1 or 2 solutions depending on the value below the square root (called the discriminant):

- If the discriminant is negative there are no solutions → the ray misses the sphere;

- If the discriminant is zero there is one solution → the ray shaves along the surface of the sphere, hitting it in exactly one point;

- If the discriminant is positive there are two solutions → the ray goes fully through the sphere and hits its surface while entering and exiting the sphere.

Optimizing the yet-to-be-implemented sphere intersection method

Although we can already implement the intersect method as it stands, there are some easy optimizations we can do to simplify and speed up the calculations.

First off, notice how the $b$ term we got from our quadratic function has a factor of 2 in it. We can use this to our advantage by simplifying the abc-formula even further when we consider $b = 2h$:

\[\frac{-2h \pm \sqrt{(2h)^2 - 4ac}}{2a}\] \[\rightarrow \frac{-2h \pm 2\sqrt{h^2 - ac}}{2a}\] \[\rightarrow \frac{-h \pm \sqrt{h^2 - ac}}{a}\]The $b$ term now changes to $h = \overrightarrow{D} \cdot (O - C)$.

Next, consider that a the dot product of a vector with itself is equal to the squared length of that vector. We got an $a$ term which states $a = \overrightarrow{D} \cdot \overrightarrow{D}$, so we can rewrite this part as $a = ||\overrightarrow{D}||^2$. But wait… In the project, we ensured that the directional vector of a ray is always normalized! This means that its length will always be exactly 1, no matter in which direction it points:

\[a = 1^2 \rightarrow a = 1\]Awesome! The $a$ term is now a simple constant, so there’s no need to calculate it. In fact… We don’t need it anymore at all:

\[\frac{-h \pm \sqrt{h^2 - 1c}}{1}\] \[\rightarrow -h \pm \sqrt{h^2 - c}\]Okay… I think this is as fancy as we can get for now, let’s get it implemented (finally!):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

#include "precomp.h"

bool sphere::intersect(const ray& r, intersect_data& data, float t_min, float t_max) const

{

// O - C

// D . (O - C)

// (O - C)^2 - r^2

float3 oc = r.origin() - m_center;

float h = dot(r.direction(), oc);

float c = sqrLength(oc) - m_radius * m_radius;

// h^2 - c

float discriminant = h * h - c;

// if the discriminant is negative, there was no ray/sphere intersection

// calculate the square root afterwards

if (discriminant < 0.0f) return false;

float sqrt_discriminant = sqrt(discriminant);

// abc-formula, try shortest distance solution first

// if both solutions fall outside the given boundaries, reject the intersection

float t = -h - sqrt_discriminant;

if (!between(t, t_min, t_max))

{

t = -h + sqrt_discriminant;

if (!between(t, t_min, t_max)) return false;

}

// update the intersection data

// the normal of the sphere is the vector between the intersection,

// and the sphere's center

data.t = t;

data.point = r.point(t);

data.set_front(r, data.point - m_center);

// the ray intersected with the sphere

return true;

}

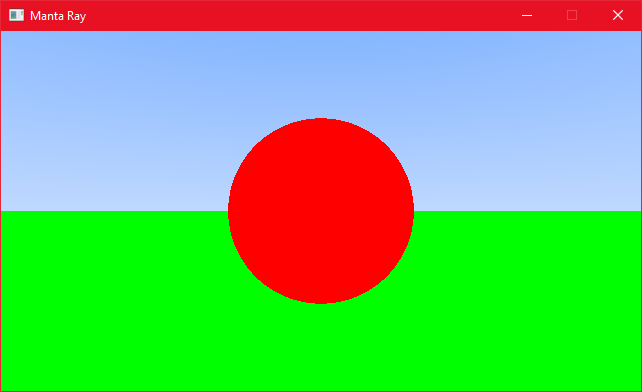

Initializing a new sphere object in mantaray.cpp gives the following result:

What about a red sun to complement the scene?

What about a red sun to complement the scene?

Triangle time

One more primitive should do it for now! And it might be the most important one, as pretty much everything in graphical applications consists out of the darn things. Once again we inherit from the intersectable class.

A triangle is defined by 3 vertices (3D points that define the corners of the triangle) and we’ll add a centroid as well, which is the point in the very center of the triangle:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

#pragma once

class triangle : public intersectable

{

private:

float3 m_v0, m_v1, m_v2;

float3 m_centroid;

public:

triangle() {}

triangle(float3 v0, float3 v1, float3 v2)

: m_v0(v0), m_v1(v1), m_v2(v2), m_centroid((v0 + v1 + v2) / 3.0f) {}

virtual bool intersect(const ray& r, intersect_data& data, float t_min, float t_max) const override;

};

As for the triangle specific intersection method, I uh… “borrowed” it from Mr. Möller and Mr. Trumbore; the Möller-Trumbore intersection algorithm. There’s no reason to re-invent the wheel when bright minds already figured out a fast solution, so let’s just use that algorithm and get this show on the road:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

#include "precomp.h"

bool triangle::intersect(const ray& r, intersect_data& data, float t_min, float t_max) const

{

float3 edge1 = m_v1 - m_v0;

float3 edge2 = m_v2 - m_v0;

float3 h = cross(r.direction(), edge2);

// calculate 'a' first, if it's almost 0 (ray parallel with triangle), return false

float a = dot(edge1, h);

if (between(a, -EPSILON, EPSILON)) return false;

float f = 1.0f / a;

float3 s = r.origin() - m_v0;

float u = f * dot(s, h);

if (!between(u, 0.0f, 1.0f)) return false;

float3 q = cross(s, edge1);

float v = f * dot(r.direction(), q);

if (v < 0.0f || u + v > 1.0f) return false;

float t = f * dot(edge2, q);

if (t < EPSILON) return false;

// reject t if the value doesn't lie between the given boundaries

if (!between(t, t_min, t_max)) return false;

// update the intersection data

data.t = t;

data.point = r.point(t);

data.set_front(r, cross(edge1, edge2));

// the ray intersected with the triangle

return true;

}

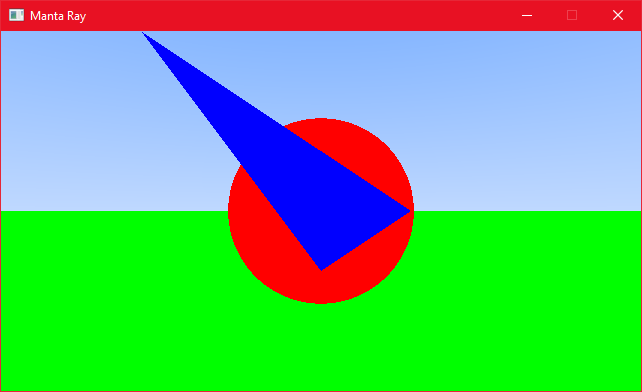

Popping a triangle object in the scene gives us the final result for this post:

I’m all out of witty remarks. Random blue triangle, that’s about it!

I’m all out of witty remarks. Random blue triangle, that’s about it!

Well, I’m supposed to be writing a post, not a book. 📚

I should probably cut it off riiiiight about here for now. Next time we will add another layer of abstraction by creating a list of intersectable objects, before diving into pretty ray tracing stuff for realsies.

Congratulations on making it through this math explosion, see ya next time!